Albert Edward Murray was born on the 11th May 1849 in Dublin, the second son of William George Murray. The Murrays were a County Armagh family of planters... ...

Albert Edward Murray was born on the 11th May 1849 in Dublin, the second son of William George Murray. The Murrays were a County Armagh family of planters from Scotland, who became an architectural dynasty.

Albert’s grandfather, William Murray, was the first architect in the family.

William, the elder, was a first cousin of Francis Johnson, renowned 18c. architect.

William became a partner to Johnson in 1819, succeeding him upon his death.

William was architect to the Irish Board of Works, Bank of Ireland, the Great Southern and Western Railways and the old Dublin and Drogheda Railways. His best known work is probably the College of Surgeons on St. Stephen’s Green. He died in 1849.

William’s son and Albert’s father, William George Murray, succeeded his father’s practice and amongst his legacy is The Royal Marine Hotel in Bray, Gilbey’s Offices on Sackville Street, Standard Assurance Offices, Scottish Equitable, The Old’s Men’s Asylum in Leeson Park, Waterford Railway Station and the Royal College of Physicians in Kildare Street. William, the younger, died in 1871.

Albert Edward, the third generation, was apprenticed to his father’s practice in 1866 and succeeded his father’s practice in 1871. He joined the Institute of Architects in 1867, eventually being promoted to Honorary Secretary for 17 years and Honorary Treasurer for 13 years. Upon becoming Secretary, the Institute’s fortunes were at a low ebb, boasting 20 members and non-existent funds. In order to salvage it, Murray moved the Institute to his office at Dawson Street, where he provided clerical services free gratis.

He managed to grow the membership some fivefold, from 20 to 100.

He also revived the Irish Architectural Association in 1896.

During his architectural career spanning over fifty years, Albert completed 85 commissions. A half dozen or so of these works became emblematic and lasting testaments to an idiosyncratic style. Whereas the style was not untypical of the late Victorian era, Albert made one small quantum modification which set this collection apart. This highly decorated and modelled style can be typified by the building now known as The Dublin Central Mission, Chancery Place, Dublin. This building, built in 1909, and designed by George Palmer Beater, features all of the elements found in the late Victorian fashion of the day ; the projecting box-bay framed with red brick pilasters, paired windows with recessed and moulded terra cotta panels above a continuous profiled cill detail, and all leading up to a central Dutch gable with a moulded pediment and elaborate coping on either side. The best and most complete collection of such buildings can be found on the Eastern side of Upper Baggot Street in Dublin. In the centre of this terrace is Albert Edward Murray’s piece de resistance, The Royal City of Dublin Hospital. Whereas Baggot Street Hospital was in the same mould and included all of aforementioned elements of the vogue of the day, there is one significant difference which distinguishes Albert’s signature.

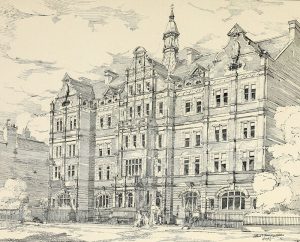

The small, but significant, difference between this established style and Albert’s hallmark was first employed in The Working Boy’s Home and Harding Technical School on Lord Edward Street, Dublin ( see below ). This building was built in 1891 and functioned as a hotel for Protestant working boys from 1892 to 1987. The hostel was established to “ afford comfortable and healthy lodgings at cheap rates for boys earning their bread “ and boasted a gymnasium club, cricket team and bell-ringing club for Christ Church Cathedral. Commentators frequently refer to the “ stone engraving of the youngster “ in the spandrel panel above the entrance door. Correspondents often refer to Murray’s buildings as being of “ carved York Sandstone and red brick “. In fact the buff components are yellow terra cotta castings from moulds unique to the brick works and quarry of Messrs. Dennis of Ruabon in Wales, and the brick is more orange than red. These decorations were previously carved in Red Sandstone, as in the Dublin Central Mission. As the yellow and orange palette was so distinctive, the wags of the day came to refer to Murray’s buildings as “ Murray’s Mellow Mixture “. Murray’s Mellow Mixture was a popular pipe tobacco manufactured in Belfast up until 1940.

As there was no Welfare State in the nineteenth century, charitable institutions were often private philanthropic initiatives, such as the case with the Harding Boys Home. Similarly, Baggot Street Hospital was established by a private trust in 1832. It was extended and the current façade added between 1892 and 1893 to the design of A.E.M. ( see below ). It was executed in the buff terra cotta and orange brick from Dennis of Ruabon. It was renamed The Royal City of Dublin Hospital in 1900 to coincide with the visit to Dublin of Queen Victoria.

Murray’s third exercise with Dennis’ catalogue of parts was the new wing onto the Rotunda Hospital, on the West side of Parnell Square ( see below ). The Rotunda was, at the time, the most famous maternity hospital in Europe, and had been built in 1745 out of the purse of the famous philanthropist, Dr. Bartholomew Mosse.

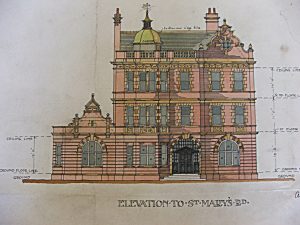

Murray’s fourth foray in his “ mellow mixture “ came via yet another medical project, and an annex to his Baggot Street tour de force. He designed The Nurses’ Home for Eastmoreland Place, to the rear of Baggot Street Hospital in 1900 and it was built in 1901. Here below, is Murray’s original drawing, rendered in watercolour, courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive.

What is particularly interesting about this drawing is the loose and incomplete doodles of the dilettante, gentleman, architect. One can only assume that the details were elaborated, and the geometry refined, by the craftsmen of Dennis in Ruabon. By twenty first century European standards, the minimal dimensions and scant specification notes would be viewed as an unacceptable Contract document, which would almost certainly give rise to a builder’s Request for Further Information. The single instruction “ earthenware ridge tiles “ and the lone word “ copper “, are not much to go on. Notwithstanding this, the drawing does have a certain charm. The freehand pencil outlines and the darker wash emphasising the shadows are a timeless connection to the hand of the architect over one hundred years ago and a refreshingly human touch in the current era of soulless computer generated imagery.

The following year, 1902, saw the construction of Drummond’s Seed warehouse on Dawson Street ( see below ). Dawson Street, at the time, was a curious mix of humming commerce which included insurance company offices, retail and a considerable number of merchants’ trading warehouses. The façade on Drummond’s is a prototypical Victorian exercise in modesty and propriety. At the same time as social mores expected women’s and piano legs to be covered up, this building is a classic example of a utilitarian building clad in an elaborately decorated exterior. Here is a photograph of the building taken in 2017. This is quintessential Albert Edward Murray.

My study of A.E.M. was sparked by a commission in 1989 to convert his Nurses’ Home from hostel to hotel. I assumed, like many, that the buff parts were York Stone. One day when scrambling along the roof parapet gutter I noticed the word Ruabon stamped into the coping tile. The inverted impression immediately conveyed a mark in a soft material, presumably hardened subsequently in a kiln. The clue led me to Messrs. Dennis of Ruabon in Wales, where they quarried the yellow clay and cast the parts in wooden moulds. In response to the original watercolour by A.E.M., here is the watercolour prepared by Edmondson Architects in 1989 to represent the gentrification of his building.

What was equally interesting about this building when we first inspected the interior, was the echo of the odd juxtaposition put forward in Drummonds, of the decorative exterior masking a functional interior, devoid of marble fireplaces, elaborate staircases or detailed plasterwork. Indeed the interior was a rabbit warren of modest, monastic cells, where the provincial maidens could be housed during their education and sojourn in the metropolis.

This relationship was rekindled in 2005, when again this office was commissioned to extend the former Nurses’ Home, which was at this stage renamed, The Hibernian Hotel. Again we studied the pattern of A.E.M.’s style and the catalogue of Dennis of Ruabon and speculated how he and they might have interpreted such a challenge. Here is our computer generated image of the proposed modifications and extension which involved raising the pediment of the original single storey dining room to form a central bay and mirroring the arcuate window of same to widen the new central bay.

Unfortunately the Executive Planner, assigned to the proposal by Dublin City Council did not agree with our thesis of faithful pastiche. Equally unfortunately, pastiche has become a dirty word in Dublin commentary, and is generally now associated with unfaithful pastiche, notwithstanding endorsement under The Venice Principles. Accordingly, an alternative was “ suggested “ and justified on the basis of the accepted wisdom of that particular day, that interventions in historic structures must distinguish themselves from the original in order to present an honest record of the history. Here is the alternative which was “ proposed “, approved and built. It is now known as The Dylan Hotel.

I still sometimes wonder what Albert would have made of all of this. Whereas he was of the same mind and never looked to the original Rotunda Hospital ( 1745 ) when he conceived his extension ( 1895 ) and he never looked to the original Baggot Street Hospital ( 1834 ) when he conceived the makeover ( 1893 ). I am in two minds about it.

In the meantime, A.E.M.’s finest hour remains hiding in broad daylight and may very well succeed in becoming his lasting manifesto or testament. The Health Service Executive moved to sell Baggot Street Hospital in 2015 ( see below ; the sleeping beauty hiding in broad daylight ). This generated significant interest amongst developers at the time. For reasons unknown, it was subsequently withdrawn from the market.

This building is on the opposite side of the street to our offices. When the sun shines, the contrast between Albert’s strident colour scheme and the blue sky is so vivid, it is unreal. It is possibly one of the most photographed buildings in Ireland and regularly attracts the attention of overseas visitors who stumble upon it with fresh eye and alien’s curiousity. Given its location on one of the best streets in Ireland, in one of the best neighbourhoods in Dublin and given the majestic way it is set back from the main building line with its imperial command as a centre-piece within a unique terrace, it is destined to be a six star hotel of world class ( see below ). It cannot and will not be anything else.