I lived in Holland for six months in 1977, playing as a professional musician, having taken a year off college to indulge my second love, music. 2017 marked... ...

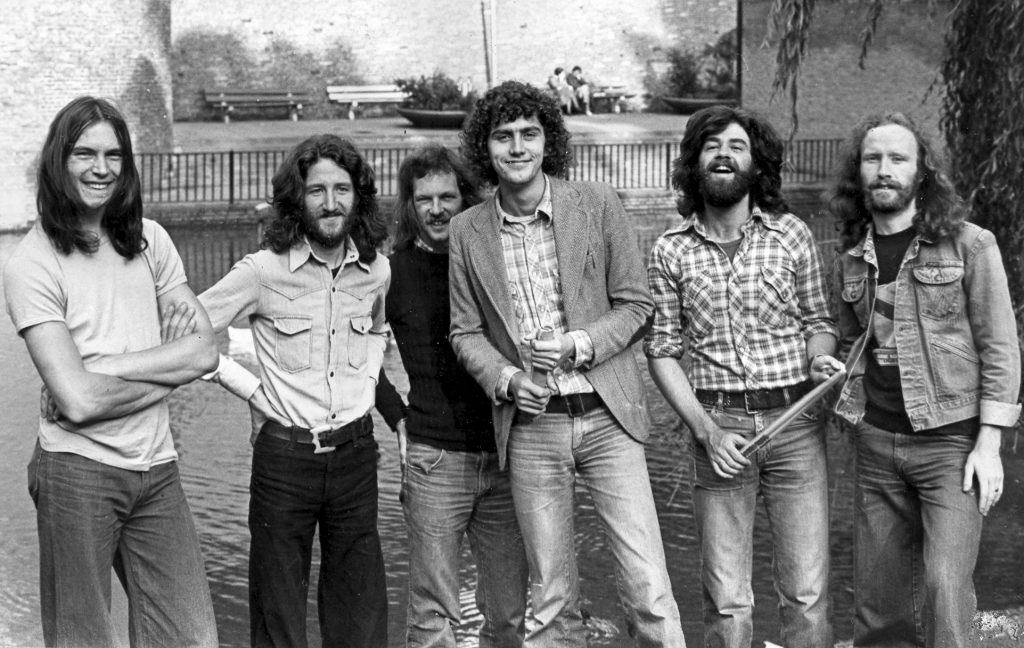

I lived in Holland for six months in 1977, playing as a professional musician, having taken a year off college to indulge my second love, music. 2017 marked the fortieth anniversary of seven wide-eyed, young, eejits from Dublin arriving in The Netherlands with a clear objective of making an indelible impression on the jazz clubs of mainland Europe.

As the souvenir re-issue of Sgt. Peppers was released this year with much fanfare and the strap-line “ . . it was fifty years ago today . . “ echoing McCartney’s lyric “ . . it was twenty years ago today . . “, so it was that it was forty years ago today and we duly had to have a re-union of sorts on Dutch soil.

Unfortunately Hurricane Ophelia delayed my return to Dublin last Monday due to cancelled flights and I ended up having to spend two days in Amsterdam, which turned out to be very useful and instructive.

I recall forty years ago, when I lived in Holland, they were a society who had obviously been urbanised a long time which had given rise to their ‘ live and let live ‘ liberal tolerance. Whereas Geert Wilders has cast a dark shadow over this Dutch disposition recently, it seemed to me that Amsterdam still had a vibrant street culture which was still ahead of us in terms of urban sophistication, to the extent that we could still learn a lot. I remember when living there, all those decades ago, being astonished to discover fully formed off street dedicated cycle-ways, with their own cycle traffic lights no less ! Considering we have only recently introduced the first wave of these strange mysterious objects with the little green flashing bicycle, it seems to me that there is still much that we could learn from these people in terms of urban grain, density and transport.

Therefore, it is not surprising to reflect that the genius who championed the concept of “ shared spaces “ in urban design, was Dutch. Hans Monderman may very well be unique in so far he is probably the only Traffic Engineer, ever, to be awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Philosophy. I had the pleasure of meeting him about ten years ago when he delivered a lecture to the Institute of Engineers in Ireland on Clyde Road.

Two weeks ago, I wrote about a different type of cycling, through the countryside and villages of Portugal, and the success of their public spaces. While I was in Holland, I had the pleasure of experiencing the urban version.

Three of our number stayed in Holland forty years ago, embraced the Dutch lifestyle and embraced a few Dutch ladies, and settled down with both.

The flautist in our band, John Devitt, took us for a cycle in Nijmegen to see an astonishing work of civil engineering which touches on two subjects close to Irish hearts at the minute, flood defences and public realm.

The trip took us over the bridge across the Waal, which makes up two thirds of the Rhine. The bridge may look familiar, as it is the bridge used as a set for the movie A Bridge Too Far based on the Cornelius Ryan book, which in fact documents a second world war story based around the identical bridge fifteen kilometres away in Arnhem.

The Dutch engineers sought to excavate a belly of earth nearly as big as the Waal itself as a parallel sump beside the river on the flood plain in order to remove surplus capacity from the Waal in the event of a flood swell. With their inimitable imperative, they arranged cycle-ways and pedestrian paths across the new bridge sections.

Even the stairs down to the new river-bank facilities has a track in order that you can wheel your bicycle down. These are thoughtful, simple and inexpensive details which open up access to every conceivable space.

Those canny Dutch engineers built an accessible flat cycle-way along the river,

and a stunning one along the top of the dike ;

. . but the piece de resistance is a cycle-way and pedestrian amphitheatre on the banks of the flood relief reservoir.

Several things struck me about this space, all of which are handsome reminders of the key strands of ‘ shared spaces ’, as espoused by Hans Monderman. Monderman spent most of his later years successfully convincing town traffic engineers to dispense with kerbs, divisions, barriers, signage and traffic lights,

and instead pave the entire cross-roads with a single surface denoting equality between pedestrians, cyclists and vehicles. He argued that on entering such a space, car drivers immediately slow down, unsure of their rights and responsibilities, and instead resort to natural caution, eye-contact and humanity.

He argued that city streets are such a chaotic clutter of visual noise in the form of signage, that most spend more time trying to read this bewildering barrage of information, than taking care of other road users and pedestrians, particularly the elderly, children and dogs. He argued that traffic lights and divisions in the form of kerbs between pedestrian paths, cycle-ways and roads

dehumanised everyone, giving each a sense of righteousness which we see on a daily basis in Dublin ; pedestrians screaming at cyclists to get off the path and cyclists screaming at car drivers for clogging up the cycle-ways. Every time the traffic lights turn green, the occupants of these insular glass bubble-cars blast their horns, move it, let’s go and get out of my way. Cycling around the narrow streets of inner Amsterdam (where there are shared spaces and no traffic lights) functions like a swarm of drones, a flock of birds or a colony of bats avoiding each other in split second timing by radar, sound or echolocation, except that humans use eye-contact. Monderman found that motorists on approaching a village cross-roads where there is no signage, no speed limits, no stop signs and no traffic lights, will slow to a stop and communicate to other roads users by facial expression or manual signals as to who is giving way or who is proceeding.

He even proved by statistics that road traffic accidents were less at shared space junctions than conventional ones. He argued that the terms car-driver, taxi-man, cyclist, trucker and or pedestrian were racist divisions in the natural order which empowered members of each sect to look down on and even abuse other sects.

Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s new film, The Vietnam War, deals with questions of dehumanisation. They interview combatants on both sides of the conflict only to find the same prejudice when groups oppose, but also the same fascination at similarities in humanity when individuals come face to face. The Vietcong interviewed were amazed to note that the evil American devils cried when one of their number died, tended to their wounded and carried injured and corpses to refuge without regard for personal safety ! Sting wrote a song at the height of the Cold War entitled “ because the Russians love their children too. “ !

Hans Monderman regrettably died young, at the age of 62, in 2008, but he can be very proud of his legacy…

and he would applaud the absence of barriers, divisions and unnecessary signage on this waterside space at Nijmegen.

This spectacular space leads up to a spanking new elegant bridge which crosses the reservoir in great style while it’s stainless steel hand-rail is reflected below.

At the entrance to the bridge, I saw a fulcrum of Monderman wonder. Cars, bikes and pedestrians mixed on a shared space and everything flowed like clockwork. No-one was knocked down, no-one got angry and no-one was blasting their horn. There was no sign saying “ watch out ice-cream van = children flocking and pensioners wandering ! “ It was pretty obvious.

There were no signs anywhere on the water-side space saying “ take care, water is wet “ or “ take care ; amphitheatres are terraced spaces with steep drops “.

In many respects, Monderman was way ahead of his time. There is a current debate about the Nanny State, and that perhaps Health & Safety has gone too far, in so far as it strips us of personal responsibility. I know that fifty years ago, if I had fallen in the river or inadvertently rolled down an amphitheatre, my old man would have said “ What did you do that for ? Why don’t you look where you’re going ? “ He wouldn’t have been taking photographs of the absence of signage in order that he could sue the County Council. There is a parallel debate raging around the question of political correctness. The question is posed, “ has political correctness removed our kids from reality and left them unable to face the underbelly of the human condition in the real world ? “.

Instead of this nightmare world of restrictions and cotton-wool, what I saw at Nijmegen was a sociable world of leisure and recreation.

Cyclists mixed with pedestrians and both mixed with vehicular traffic.

Kayaks take off around the bend. Paddle-boarders unload on the slip-way.

Rowers train on the water dodging barges.

They say that Amsterdam is the original cycling city. I have to confess that I saw a bewildering array of new iterations which apparently pass for bicycles.

As to where we are now, I wonder will the Nanny State continue unabated to the point where dehumanisation leads to a total abrogation of personal responsibility ?

So sad that Hans Monderman was taken from us early, just when his mission was gaining traction.

I wonder would he take any comfort in the predictions of the near future. Whereas the automotive industry already has the technology for autonomous vehicles, the current race is on to formulate and make standard a V2V language such that vehicles can talk to each other, tell each other where they are going and form into “ trains “ of ten or fifteen pods grouped together to save road space and fuel.

More important, is the parallel race among governments, local authorities and police forces to formulate and make standard a V2i language such that these trains can talk to the city and arrange their journeys according to social responsibility.

At this point, one of Hans Monderman’s pet ambitions will become a reality as traffic lights, speed limits and stop signs disappear, to be replaced by boxes under the pavement which transmit signals to the vehicles.

At this point his argument that our cities will be better for the elimination of visual noise will become a reality, but his bigger ambition that we should take back personal responsibility will be lost, because better decisions will be taken in micro milli-seconds by machines.

At this point eye contact and social interaction will be lost again. Sorry Hans.