If its Christmas, it must be Frank For most of my adult life, my ex. and myself spent Christmases with my old friend Frank Fitz. and his wife,... ...

If its Christmas, it must be Frank

For most of my adult life, my ex. and myself spent Christmases with my old friend Frank Fitz. and his wife, because Frank and I married two sisters. Some say we mustn’t have had a very wide circle of friends ! Anyhow, so it is in my divorced state, that the past two Christmases I have found a new Frank, . . the Lloyd Wright. The man, who, when an interviewer put it to him that “ some have said you may be the greatest living American architect ! “, replied “ not may, but I am the greatest, living or dead, and not just in America but in the whole world ! “. Modesty was obviously something which Frank was not blessed with. On the other hand, as Hitchcock once said, a modicum of arrogance is a pre-requisite in order to be able to direct, conduct the orchestra or steer your vision through to realisation, by leading a design team, managing the builders and negotiating the client’s spouse and their bank manager, while at the same time keeping the Fire Officer happy.

On visiting my sister in Washington D.C. last Christmas, I had the great pleasure of fulfilling a 45-year yearn to complete the pilgrimage to Fallingwater in Virginia.

This Christmas, in order to sustain the new habit, I had the pleasure of visiting F.L.W.’s Hollyhock House in Los Angeles, while on a very restful, yuletide-sojourn with my old school pal, James Lancaster and his very hospitable, thespian family.

While ticking off two essentials on any architect’s bucket list, these twin projects got me to thinking about the dreaded private house commission. It’s a funny old species, because, whereas most architects start out in life doing house extensions for family friends ( or re-modelling as they call it in the States ), these eventually lead to that next rung on the ladder, a private house on a greenfield site. Now, these projects offer up mixed emotions in retrospect. It is inevitably thrilling to practice on your first blank canvas, but the excitement can at the same time obscure the fact that this monument to that family’s aspirations may be a rare opportunity to give expression to their own collective disposition. In this way these projects are minefields for the inexperienced. It was drilled into me as an apprentice that architecture is a profession whose raison d’etre is to serve the purpose of the building. In this case, the purpose is a once-off articulation of the clients’ brief which ought to be borne out of their individual lifestyle. Therefore, it is expected that the quality of the relationship between client and architect should form the backbone of the best outcome. The aforementioned two F.L.W. cases appear to be excellent examples of a successful collaboration and a less satisfactory end result.

Fallingwater is a spectacular and arresting sight. Can I suggest, for the purposes of the argument, that it was the strength of the relationship between Frank and the Kaufmanns that led to its success, or were there other factors at play which resulted in the triumph. Was it perhaps Frank’s intuitive response to the special context offered by such an extraordinary site, or was he emboldened by sensing the special place that their weekend retreat held in their hearts ? Was it a rush of creativity borne out of his failing career at the time and the drought of work which preceded it, or was it the reverence in which the Edgars Kaufmann held the architect which strengthened his hand to lead and succeed. Here is the delicate balance between professional and client. The responsibility of the architect to understand the clients’ requirements, and the trust of the client to allow him guide them and forge a unique response from first principles. It is equivalent to the doctor / patient relationship established over many years of consultation when the medic knows that on this less serious occasion the patient is not likely to follow his or her treatment, and where at another time the professional must save the client from themselves and insist that the patient go straight home to bed. Sometimes, the architect has to step in and prevent the unwise choice of a client or a misappropriation of some applied solution. Equally the client must play their part and participate in the process of assisting the design to develop of its own accord.

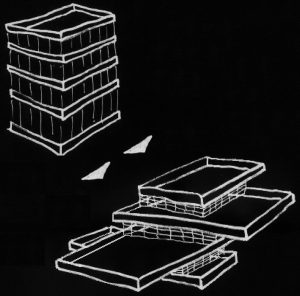

While domestic work was drying up in Chicago for Wright, Bauhaus in Germany had become the centre of the universe ( 1919 – 1933 ) and Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye had asserted the potential of reinforced concrete as the new medium, liberating architectural form from load-bearing masonry. In 1934, Ezra Pound had espoused “ Make It New “, heralding modernism. Wright felt that Gropius and Mies had stolen the limelight, leading to the ultimate stack of baking trays alternating concrete and glass bands to form the ubiquitous modern office block. The pendulum had swung to the classicist language of stripped-down modernism. Wright needed to wrest the narrative back to the romantic, and in 1935, with Fallingwater, he rotated, projected and re-arranged those baking trays in a masterful exhibition of artistic craftsmanship. He had re-imagined the European palette of elements in a more sculptural form adapted to a rustic setting far removed from the mundane urban rhythm. In one bound he had made the creative leap from uniform machine to domestic jungle, and allegedly completed in the two hours between, a phone-call announcing Kaufman Senior’s unscheduled visit to inspect the drawings ( which he had been told were well advanced months earlier ), and Senior’s appearance.

There is some evidence that Kaufman and his architect had moments of disagreement. For example, the client had visualised the house on a flat area looking back at their favoured waterfall. He was disconcerted when he discovered that Wright had placed the house on top of the waterfall. But then most departures from convention are met with some shock and subsequently appreciated for their originality. We had a case recently where the Planner took one look at the drawings and said “ I’m not sure about that finish on a house . ; I’ve never seen it before “. I naturally replied “ . . is . . that . . not . . good ? Why else, would you employ an architect. If it had been done before, you could cut and paste and do it yourself. “ After a judicious kick on the shins under the table from my client, we folded our tent, and, of course, the Planner prevailed and we clad it in brick as requested ! Anyway, I find that Kaufman and Wright were invariably good for each other and the outcome is testament to that.

Conversely, Barnsdall House, appears to me, to be too literal, and the reference to the Mayan pyramid decorated with Hollyhocks seems to have become the main imperative, while the needs of Wright’s client, Aline Barnsdall took second place. There is evidence that their relationship was fraught and unsatisfactory, and this supports my thesis. Those with more money than sense are the worst. We’ve all had difficult clients and the outcome is invariably unconvincing. The architect of course is never to blame, but an untenable relationship is. Wright variously referred to Ms. Barnsdall as, inter alia, . . “ . . a restless soul . “. It seems she had houses all over the place and had a mortal fear of settling in any one location. Perhaps that is why she participated so poorly and was only too glad to criticise every aspect of the house. If the architect is left to his or her own devices, then the outcome is bound to lack sufficient meaning to the end-user.

This is particularly true of the private house commission.

The details of Hollyhock House are out on their own. The craftsmanship is masterful. Everything is polite and perfect. It is hard to fault.

But for all that, it “ looks like “ a museum or an art gallery, because of the extensive blank masonry and Wright’s obsession with ‘ compress and release ‘, carefully arranging any windows or opes to focus on the landscape views.

In fairness to Wright, the house was intended to be part of a bigger campus including a 1,200 seat theatre, which part of the brief was not completed. It seems the spectre of the permanence of the theatre and the commitment which would have followed such a venture, spooked Ms. Barnsdall, and she took fright at the idea of putting down roots in one place. She spent very little time in the house, but spent plenty of energy on criticising the design. It was eventually abandoned and subsequently let out on lease for a different purpose.

This contrasts with the fate of Fallingwater which was adored by the Kaufmans, subsequently occupied by Edgar Kaufmann Junior and lovingly handed over to Virginia State for posterity.

Beware of the dreaded private house commission, it can be a poisoned chalice or ‘ hospital pass ‘, to use a Rugby analogy. Look deep into those client’s eyes, make sure you are on the same page. Make sure the relationship is strong enough to stand the test and deliver up something worthwhile.